The 1950's

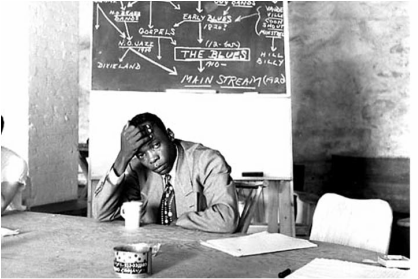

John Lee Hooker at the Roundtable © 1951 Clemens Kalischer

The brainchild of the Barbers' friend Marshall Stearns, an English

professor at Hunter College and a well-known jazz critic and historian,

the "Folk and Jazz Roundtable'' was one of the first serious inquiries

into the origins and development of jazz, which at the time was still

looked down upon by ``serious'' music lovers.

Jazz was also played primarily by African-Americans, and by inviting musicians to stay with them the Barbers tested the limits of local hospitality. "Black people were not popular in New England," remembers Stephanie Barber, who today lives in Lenox not far from the original site. "In the early days, we had problems finding beds in local inns for artists who happened to be black, when we overflowed our own capacity. People in the village did not approve of what we were doing. But in good New England fashion, they believed we had the right to do it." The neighbors' disapproval of what went on at Music Inn would be a recurring theme over the course of the next three decades.

As for the musicians themselves, the roundtables often proved revelatory. In the liner notes to the "Historic Jazz Concert at Music Inn" album, recorded in 1956, Nat Hentoff recounts the time Charles Mingus exclaimed, "Hey! I've got roots!" after one particularly illuminating solo by ragtime pianist Willie "The Lion" Smith. Dave Brubeck recalls the time Dr. Willis James, an authority on African-

American field hollers, demonstrated a field holler in five-four time. "He said that the Dave Brubeck Quartet was on the right track," says Brubeck, providing a crucial endorsement at a time when his rhythmic innovations were controversial. "That was my big moment of glory. He explained that if you go back to the field hollers, they go right back to Africa, and why shouldn't I be doing what I'm doing, that it was in the tradition of Africa to play in complicated time signatures. It didn't hurt at all to have him defend me in public." As a result, said Brubeck, he went on to record a sequel to his experimental "Time Out" album, called "Time Further Out," part of which was written at Music Inn.

As valuable as the actual content of the lectures and discussions were, they also afforded the rare opportunity for musicians, critics and scholars to live together -- this was an inn, after all -- in a casual atmosphere where music and discussion flowed freely.

"It was really in some respects like being on shipboard," says Nat Hentoff, who attended many of the sessions as editor of the jazz monthly Downbeat, "because there were really no delimitations as to hours or place in terms of when you could talk to musicians and when they could talk to each other. It was a continuous flow, extraordinarily relaxed, and that's what made it different."

Jazz pianist Randy Weston returned year after year to Music Inn, where he wrote "Berkshire Blues." He calls its impact on him "tremendous." "I got a lot of my inspiration for African music by being at Music Inn, meeting people like Jeffrey Holder, Baba Olatunji, Langston Hughes and Dr. Willis James," says Weston, whose work draws heavily on African elements. "They were all explaining the African-American experience in a global perspective, which was unusual at the time."

As participation in the annual roundtables grew, the Barbers decided to let the outside world in on the secret of what was going on at Music Inn -- attendance at the workshops was by invitation only -- by presenting a concert series. "We thought it was a just a shame that you couldn't hear wonderful jazz unless you went to some smoke-filled dive on 52nd Street or in the Village," says Stephanie Barber. "The only jobs they could get were in cellars or nightclubs full of smoke and lots of talk, where they got paid very little. We thought it would be marvelous for them to have a concert hall where they could present their music, their own Carnegie Hall."

Jazz was also played primarily by African-Americans, and by inviting musicians to stay with them the Barbers tested the limits of local hospitality. "Black people were not popular in New England," remembers Stephanie Barber, who today lives in Lenox not far from the original site. "In the early days, we had problems finding beds in local inns for artists who happened to be black, when we overflowed our own capacity. People in the village did not approve of what we were doing. But in good New England fashion, they believed we had the right to do it." The neighbors' disapproval of what went on at Music Inn would be a recurring theme over the course of the next three decades.

As for the musicians themselves, the roundtables often proved revelatory. In the liner notes to the "Historic Jazz Concert at Music Inn" album, recorded in 1956, Nat Hentoff recounts the time Charles Mingus exclaimed, "Hey! I've got roots!" after one particularly illuminating solo by ragtime pianist Willie "The Lion" Smith. Dave Brubeck recalls the time Dr. Willis James, an authority on African-

American field hollers, demonstrated a field holler in five-four time. "He said that the Dave Brubeck Quartet was on the right track," says Brubeck, providing a crucial endorsement at a time when his rhythmic innovations were controversial. "That was my big moment of glory. He explained that if you go back to the field hollers, they go right back to Africa, and why shouldn't I be doing what I'm doing, that it was in the tradition of Africa to play in complicated time signatures. It didn't hurt at all to have him defend me in public." As a result, said Brubeck, he went on to record a sequel to his experimental "Time Out" album, called "Time Further Out," part of which was written at Music Inn.

As valuable as the actual content of the lectures and discussions were, they also afforded the rare opportunity for musicians, critics and scholars to live together -- this was an inn, after all -- in a casual atmosphere where music and discussion flowed freely.

"It was really in some respects like being on shipboard," says Nat Hentoff, who attended many of the sessions as editor of the jazz monthly Downbeat, "because there were really no delimitations as to hours or place in terms of when you could talk to musicians and when they could talk to each other. It was a continuous flow, extraordinarily relaxed, and that's what made it different."

Jazz pianist Randy Weston returned year after year to Music Inn, where he wrote "Berkshire Blues." He calls its impact on him "tremendous." "I got a lot of my inspiration for African music by being at Music Inn, meeting people like Jeffrey Holder, Baba Olatunji, Langston Hughes and Dr. Willis James," says Weston, whose work draws heavily on African elements. "They were all explaining the African-American experience in a global perspective, which was unusual at the time."

As participation in the annual roundtables grew, the Barbers decided to let the outside world in on the secret of what was going on at Music Inn -- attendance at the workshops was by invitation only -- by presenting a concert series. "We thought it was a just a shame that you couldn't hear wonderful jazz unless you went to some smoke-filled dive on 52nd Street or in the Village," says Stephanie Barber. "The only jobs they could get were in cellars or nightclubs full of smoke and lots of talk, where they got paid very little. We thought it would be marvelous for them to have a concert hall where they could present their music, their own Carnegie Hall."

By the mid-'50s, concerts were regularly held under a tent in the courtyard of the renovated stables, and thus was born the Berkshire Music Barn, featuring performers like Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Armstrong, Mahalia Jackson, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Dave Brubeck, Thelonious Monk, the Modern Jazz Quartet and Jimmy Giuffre, who grew so fond of the surroundings that he never left. "There was no other place like it," says Giuffre, who still calls West Stockbridge home. "It's why I moved up here."

By 1957, the success of the roundtables and the concert series led to the creation of the School of Jazz at Music Inn, with MJQ pianist John Lewis as director. For three weeks in August, famous pros like Lewis, Gillespie, Giuffre, Lennie Tristano, and Max Roach trained a new generation of jazz players in the first formal effort of its kind. Both Arif Mardin, whose credits as a record producer include Aretha

Franklin and the Bee Gees, and Ornette Coleman, who pushed jazz to the limits of abstraction in the 1960s, were graduates of the School of Jazz. With the concerts at the Music Barn going full steam and the school blazing new trails in jazz education, Music Inn became known throughout the country as a great place to hear and play jazz. Among the numerous live albums recorded there were two by the MJQ and one by saxophonist Sonny Rollins. By the end of the decade, Music Inn was synonymous with the best in jazz.

"Jazz has often been associated with a city, like New Orleans style, Kansas City style, Chicago style," says Dave Brubeck, who liked the place so much he brought his family there to stay one summer. "But it can happen wherever the right guys get together. And a lot was happening up in Lenox. I don't think a style came out of there, but many styles were being examined, and the boundaries of jazz were being stretched up there."

In 1957, the Barbers bought and moved into Wheatleigh, the main house of the original estate, and began converting it into the palatial inn it remains today. After a few years, the demands of running both places grew burdensome, so they decided to sell Music Inn. And although the place still had two decades of life left in it, a particular era came to an end, as did a small but vital chapter in the history of jazz in America.

By 1957, the success of the roundtables and the concert series led to the creation of the School of Jazz at Music Inn, with MJQ pianist John Lewis as director. For three weeks in August, famous pros like Lewis, Gillespie, Giuffre, Lennie Tristano, and Max Roach trained a new generation of jazz players in the first formal effort of its kind. Both Arif Mardin, whose credits as a record producer include Aretha

Franklin and the Bee Gees, and Ornette Coleman, who pushed jazz to the limits of abstraction in the 1960s, were graduates of the School of Jazz. With the concerts at the Music Barn going full steam and the school blazing new trails in jazz education, Music Inn became known throughout the country as a great place to hear and play jazz. Among the numerous live albums recorded there were two by the MJQ and one by saxophonist Sonny Rollins. By the end of the decade, Music Inn was synonymous with the best in jazz.

"Jazz has often been associated with a city, like New Orleans style, Kansas City style, Chicago style," says Dave Brubeck, who liked the place so much he brought his family there to stay one summer. "But it can happen wherever the right guys get together. And a lot was happening up in Lenox. I don't think a style came out of there, but many styles were being examined, and the boundaries of jazz were being stretched up there."

In 1957, the Barbers bought and moved into Wheatleigh, the main house of the original estate, and began converting it into the palatial inn it remains today. After a few years, the demands of running both places grew burdensome, so they decided to sell Music Inn. And although the place still had two decades of life left in it, a particular era came to an end, as did a small but vital chapter in the history of jazz in America.

- Reprinted from The Life and Times of Music Inn with permission by Seth Rogovoy.

Continued... 1960's 1970's

Continued... 1960's 1970's

Music Inn Archives is a non-profit program administered by Projectile Arts, Inc.

* Website created by Lynnette Najimy of Beansprout Productions and Lee Everett of Fine Line Multimedia

* Website created by Lynnette Najimy of Beansprout Productions and Lee Everett of Fine Line Multimedia